“Very small projects”

Upon the initiative of the Taizé brothers living in Dakar, Senegal, a reception service for refugees and immigrants (P.A.R.I.) was set up in 1995, under the auspices of Caritas-Dakar. The parishes and the religious communities of the city gave it responsibility for an activity that is becoming more and more necessary as the number of displaced persons increases in this Western horn of Africa.

From the start, the P.A.R.I. has put the accent on helping these urban refugees to assume their responsibilities: it is essential that they themselves take charge of their needs and their insertion in the varied and highly developed informal sector of life in Dakar. The principal means of doing this has been through the promotion of “very small projects”.

First of all the P.A.R.I. asks the refugee by what job he feels able to assure his survival, in a context where he can expect no permanent assistance from anyone. It is the refugee himself who has to find the response to this question so that he genuinely commits himself in his project. Next, he is asked to draw up a list and an estimate for the equipment, materials, and eventually the produce that he believes he needs. The P.A.R.I. examines the project, has it amended and systematically favours those that imply a profit through the work of the person concerned. Purely commercial propositions are however usually avoided.

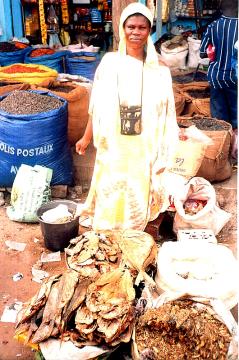

Among the most frequent projects, there is haircutting, making and repairing shoes, making doughnuts, setting up a street restaurant, working in the port or in the markets thanks to the provision of a rickshaw, etc… The projects do not exceed 30 000 Fcfa (around 45 Euros). This is a non-returnable gift. However it is never money that is handed over: it is the P.A.R.I. that purchases the material and gives it to the person concerned.

Next, the P.A.R.I. supervises the setting up of the project through regular visits. Given the mobility of many of these activities, this is no easy matter. Some who have persevered and appear particularly painstaking are given an extra “hand” after one year, especially if they are responsible for a family.

The success rate, around 60%, appears fairly satisfactory. It can happen that a refugee moves from one activity to another, selling the material provided by the P.A.R.I. No matter. What counts in the long run is that he takes charge of his life.

The P.A.R.I. does not claim that these “very small projects” provide lasting solutions for the problems of refugees, even if some people do persevere and survive for years thanks to their project. Above all this is a means of teaching people to become responsible and a practical way of giving them a leg up.

It sometimes happens that the beginning of a project coincides with a period of great difficulty for the refugee – meeting urgent needs, like food, for example – resulting in the failure of the project. Plans therefore ensure that the granting of equipment for a “very small project” is accompanied by the gift of “food support”. For people who have a family, “food support” consists of a package containing 10 KGs of rice, 1 litre of oil, 500 grams of pasta, sugar, powdered milk, and soap; to a total value of 6550 Fcfa (10 Euros).

Who are the refugees who benefit?

Who are these refugees scattered through the large built up area of Dakar? In the early years there were Rwandan families who had left Central Africa during troubles, after living there for several years. There were young Congolese from Brazzaville and from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who were under threat for ethnic reasons or else whose families were on the “wrong” side in the political struggle. There were numerous Liberians fleeing their country again, after trying to return under the illusion that peace was coming at last. There were also people from Sierra Leone, who were very numerous in times of trouble. Since those early years, the nationalities have become more diverse and the project helps not groups, but a scattering of individuals. Amongst these, it is more and more difficult to distinguish political refugees from “economic refugees” or even people who are simply migrants. They all claim to be refugees. In fact, very few of those who request asylum finally obtain the much coveted refugee status: on average only 6%! All the others, once the resources that bring a minimum of legal protection have been exhausted, are left without a residence permit (you need a regular job) or a passport (you need to be in touch with the embassy from which they keep their distance). Dakar is therefore the paradise of people “without identity papers”. If they keep quiet, do not wander about at night, and keep clear of traffickers, they can live for years in Dakar without much trouble from the police. One day perhaps, if caught up in a police raid, they might spend several months in preventive detention. After six months, the tribunal will condemn them to the length of time they have just spent behind bars and will ask them to leave the country… which they will certainly not do.

A new deal

Since 2006 things have been greatly complicated by a wave of clandestine emigration, in the many “pirogue” boats which sail towards the Canaries. This phenomenon involves mainly young Senegalese, but also some foreigners who we thought were seeking refuge in Dakar, whilst they were in fact merely “in transit”.

The P.A.R.I. does not want to encourage these mad ventures which sometimes end in tragedy, and mostly result in forced repatriation. What a waste of energy and money – which, however, illustrates the disillusionment of a section of African youth who have lost all hope and cannot envisage a future in their own country. They cope very badly with the failure of their attempt, which brings shame and, often, debt. There are even young Senegalese who do not dare to go home and find themselves a kind of refugee in their own country. They join up with other “stuck” migrants; they stay in Dakar and get by as best they can – like so many other Dakar Senegalese who are not much better off.

This is a new challenge for P.A.R.I. Many questions are raised by the consequences of clandestine emigration: the lot of those expelled and repatriated (who often dream only of setting off on another attempt). Would it be not be better to join forces with others, in making efforts towards education and development which could give back to young people the hope that there is, nevertheless, a future for them in Africa? At the same time, it will be essential to continue to accompany all these young defeated adventurers, who are so bitter and disillusioned.

What luck to be able to live this in Dakar and not elsewhere! This city offers an exceptional welcome to strangers, especially in its poorest areas. People may have little to share, but there is a great tolerance, which has even become established as a national virtue. This is the famous “téranga” (welcome) – which is no empty word.

TAIZÉ

TAIZÉ